The first part of this article, How I Trashed My Testosterone, received a tremendous response. I’ve discovered that many men share my concerns, from young elite athletes to aging weekend warriors.

In Part I, I identified the key factors that led to my troubles with T:

- chronic overreaching in training

- underfueling workouts

- dietary risk factors

- insomnia

- stress, anxiety and low level depression

If I had set out to trash my testosterone, I would have been hard-pressed to do a better job. I screwed up big time, but I’m bouncing back much stronger and smarter. In this article, I’ll share the holistic, science-based approach I’m taking to recover from low T. This is by no means intended to be a comprehensive guide, but rather my own case study.

If truth be told, this post is a tad premature. I’m still waiting for my next blood test to confirm that I am in fact on the right track. But the steady reversal of the symptoms described in Part I leaves little doubt in my mind.

Training & recovery

Not surprisingly, there is a good deal of evidence that overtraining/overreaching/under-recovery can decrease T levels [1,2,3,4,5,6]. I paid lip service to the idea of “training smart”, but a major hurdle for any self-coached athlete is the absence of an objective perspective. Too often, there was a disconnect between what I thought I was accomplishing and what I was actually doing. This year, I was finally ready to hand over the reins to two very capable coaches.

Less training, more recovery

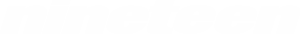

The biggest change my coaches made was dialing back my training load and prescribing more recovery time. Like many endurance athletes, I gravitated towards training fairly hard most of time, plugging away with more or less the same training load most days, weeks and months. My monthly training volume in 2013 is shown below and a graph of my daily training load would be similarly flat.

|

| 2013 monthly training volume. Average monthly volume was 85 hours. From: Pseudo-Pro Training: 2013 in Review |

This type of relatively constant, unrelenting training is termed “high monotony” training, and is a risk factor for overtraining, illness and injury [1,2,3]. I identified this problem in January 2013 (Lessons from Overtraining: Microcycles, Macro Mistakes), but failed to make significant changes on my own.

One radical change my coaches made was introducing one day completely off training per week. Not even a little “recovery workout”. Nada. Ideally, I’m even supposed to avoid anything triathlon-related on my day off. As an athlete who averaged only a couple recovery days per year in the past, I was at first reluctant and skeptical, but I was soon a convert.

My weekly off day allows me to muster the physical and mental energy to really get after my training the rest of the week. I can also turn my attention to other activities that otherwise get neglected. I now firmly believe that there is no substitute for complete rest.

Downtime

Another radical departure from the past was taking my first real downtime in nearly a decade. My coaches and I had originally thought that I might require several weeks away from the sport to allow my endocrine system to fully recover, which would torpedo much of my 2014 season. Thankfully, I responded rapidly to the changes described here, but my coaches still insisted on 10 days of deep recovery in July following my first phase of the season. It would be a lie to say that I enjoyed this time, but I accepted my penance and lived to tell the tale.

Strength Training

Another important change was the introduction of quality strength training several times per week (weights, plyometrics, band work). The evidence supporting the direct benefits of resistance training for endurance sports is equivocal [1,2]; however, the testosterone boosting effect of resistance training is well established [1,2,3,4,5,6,8]. It can therefore help counteract the effects of chronic endurance exercise, which tends to lower T levels in men [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

Energy balance, fueling & weight

One of the most important factors contributing to my low T eluded me for the longest time. From 2009 to 2012, there is little question that I did not eat enough, period. I never starved myself, but my sorely misguided “less is more” mentality regarding food and weight led to restrictive eating habits. I discussed this revelation in Fatter & Faster? Finding My Racing Weight.

I purposely increased my weight from a low of ~62.5 kg (~138 lbs at 1.82 cm, 6 ft tall) in 2012 to my current weight of ~70 kg (154 lbs). And it wasn’t all muscle. I’ve erred on the side of caution and stopped attempting to directly manipulate my body weight and composition. Low body fat or body fat losses may be risk factors for low T [1,2], so recovering from low T is not the time to cut down.

But the real surprise was that total calories and body weight weren’t the entire problem. Until May 2014, I scarcely fueled any workouts. Of the 15-25 hours of training I did per week, I only occasionally lightly fueled my long rides. I did countless hard 2-3 hour workouts on water alone.I’m not exactly sure what I was thinking, but I seemed to be getting away with it. Compared to others, I’ve always had an almost freakish ability to perform without fuel or even fluids during long workouts.

I gained a major insight from working with a brilliant sports doctor. As luck would have it, she was the lead author of the IOC consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), which we now believe was a major cause of my low T.

“The syndrome of RED-S refers to impaired physiological function including, but not limited to, metabolic rate, menstrual function [or hormonal function in men], bone health, immunity, protein synthesis, cardiovascular health caused by relative energy deficiency. The cause of this syndrome is energy deficiency relative to the balance between dietary energy intake and energy expenditure required for health and activities of daily living, growth and sporting activities. Psychological consequences can either precede RED-S or be the result of RED-S.”

Put simply, the amount and/or timing of my food did not meet the high energy demands of my training. Constantly underfueling workouts was harmful. This came as a surprise, but is now painfully obvious.

The fact that my weight was stable or increasing over the past two years was a red herring. That suggests that my energy balance over the course of days and weeks was probably fine, but it turns out that energy balance matters on a finer timescale.

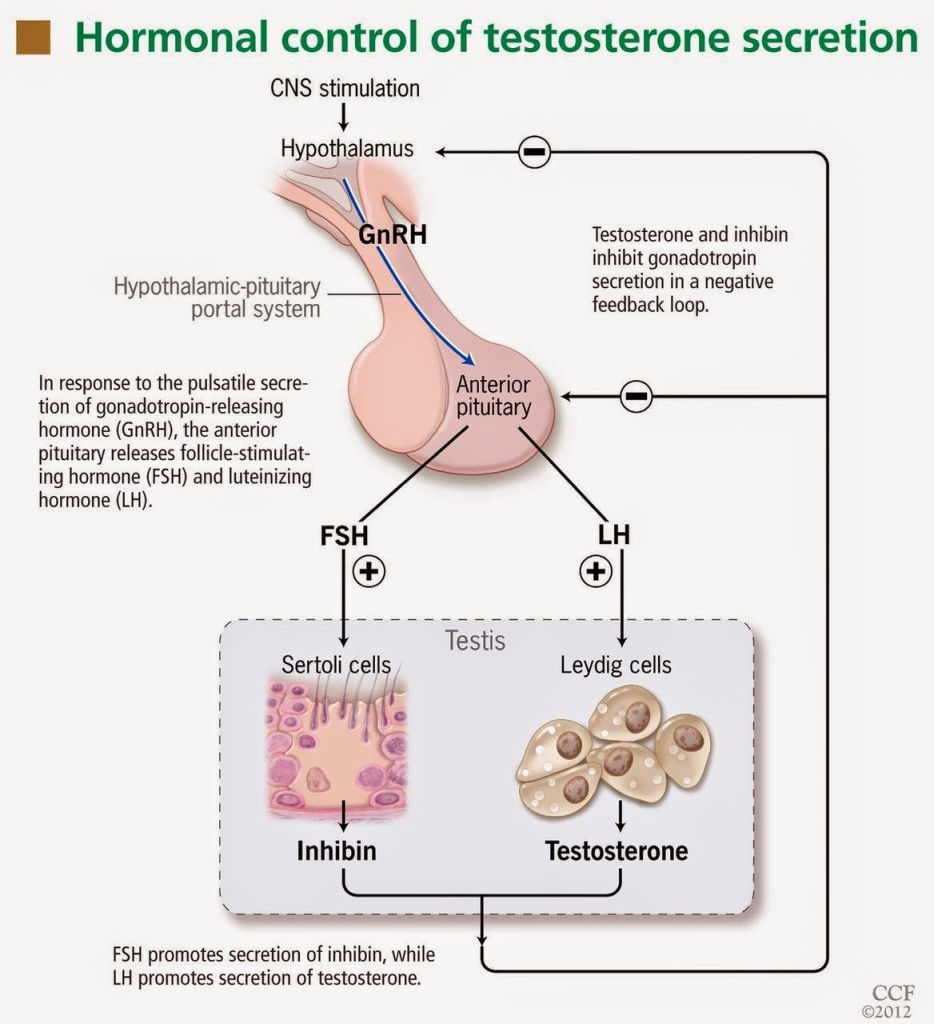

By under-fueling long workouts, I was repeatedly depleting my glycogen stores and putting myself into short-term energy deficits, often amounting to thousands of calories which were not replenished until many hours or days later. The doctor explained that my body may effectively react as it were in starvation mode and shut down non-essential functions, such as sex hormone production. Repeatedly starved of energy, my brain’s hypothalamic-pituitary complex got lazy and neglected its duties!

|

| A figure from an excellent primer on the diagnosis, mechanisms and causes of low T: Male hypogonadism: More than just a low testosterone. My levels of luteinizing hormone (LH), a hormone secreted by the pituitary gland which stimulates T production as part of a negative feedback loop, in addition to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), were “inappropriately normal”. |

My new policy is to appropriately fuel all workouts longer than 1.5 hours, and some shorter ones, whether or not I feel like I need to.

As a sidenote, my fueling practices (or lack thereof) were in effect “glycogen depletion training”, a decidedly risky technique that may also carry some benefits (under specific conditions for some athletes) [1]. My unintentional long-term experiment may have produced an interesting metabolic adaptation. I suspect that years of glycogen depletion training taught my body to use a greater proportion of fat during endurance exercise, which may be desirable for long course racing because it spares limited glycogen stores [1,2,3,4,5]. Without a clone to serve as a control in this experiment, I’ll never know for sure!

Nutrition & supplements

Disclaimer: Consult a dietitian or doctor before taking supplements or modifying your diet.

As previously discussed, the quantity and timing of food was probably my biggest issue, but there was also room for improvement in my nutrition. Beginning in 2009, I followed a lacto-ovo vegetarian diet. Health was never my motivation and I’m not convinced that vegetarianism is any more or less healthy than a regular diet. A vegetarian diet requires more effort and attention to detail, particularly for athletes.

There is no definite relationship between T levels and meat-free diets. Studies have reported both higher [1,2] and lower [3,4,5] total T and little to no effect on free T [1,2,3] in vegetarians and vegans compared to omnivores.

I suspect that shortcomings in my diet contributed to my low T and I have made the following changes:

- increased the fat and cholesterol content of my diet

- started supplementing:

- zinc

- vitamin D

- fish oil

- added fish/seafood back into my diet

- eliminated nearly all soy

- started drinking more coffee

Countless dietary practices and supplements are claimed to boost T, but my research suggested that most are based more on broscience than peer-reviewed research (banned substances notwithstanding). The scientific basis for each of the changes I made, including some test results, is discussed in an appendix at the end of this article.

I also supplement iron because my blood tests have shown that my intake or absorption is insufficient, which reintroducing fish/seafood should help. Testosterone is also implicated in iron metabolism [Appendix]. Another recent change is supplementing whey protein as a convenient complete protein protein source to support my semi-vegetarian diet.

Sleep

Sleep and testosterone are mutually influential. There is a good deal of evidence that sleep loss disrupts T levels and that low T levels can disrupt sleep quality or patterns [1,2,3,4]. In this way, poor sleep and low T can form a vicious cycle, as I believe they did in my case.

From about 2010-2013, I suffered from chronic early morning insomnia, which at its worst, saw me awake before 3 AM every day. Which came first, insomnia or low T, is a “chicken or egg” question, confounded by the fact that both issues had other simultaneous causes.In 2013, I got serious about my sleep issues with a multi-strategy approach described in a two-part article: How I Kicked Chronic Insomnia: Part I & Part II. I now routinely “sleep in” until 5:30-6:00 AM, which is almost normal!

|

| Daily wake up time in 2013. The general trend is in the right direction, but my insomnia didn’t disappear overnight. I didn’t start collecting data until the worst had passed (3:00 AM wake ups). |

Mental health

My university years between 2008-2012 were marked by stress, anxiety and low level depression. The university environment proved to be toxic for me, but my stubbornness and self-isolation were as much to blame. Self-reflection and hindsight produced The Perfectionist & the Elephant in the Room, which captures my frame of mind at the time:

“Driven by an irrational fear of failure, I poured myself into studying and training with compulsive intensity. . . . As my anxiety showed no signs of abating, I leaned more and more heavily on the crutch of training. It was the only way I could temporarily quiet the dull roar of anxiety.”

Again, the interplay between mental health, low T and the other factors described here is a tangled web. It has been observed that psychological stress can reduce T levels [1,2,3,4,5] and that low T is associated with depression, anxiety and decreased quality of life [1,2,3,4,5].

Graduating in 2012 marked a turning point in my mental health. It’s hard to say whether it was a lifestyle change, maturation, finding meaning in triathlon and work, connecting more with people, monitoring and managing stress, practicing gratitude, or deliberately relaxing and being less self-critical. Whatever the causes, I now find myself much happier and more grounded.

A word on anti-doping

A few people have joked that my low T (as well as my relatively low hematocrit: 41% in May) make me an ideal candidate for doping. My issues have given me a personal interest in the anti-doping crusade in endurance sports. The fact that I’ve had to pursue the slow, natural route to recovery while some other athletes simply reach for a syringe is a bitter pill to swallow.

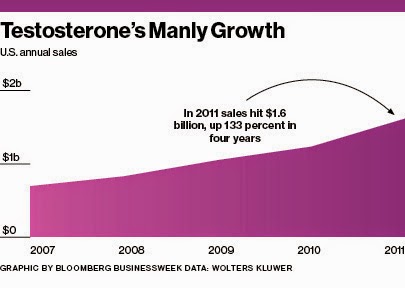

Indeed, with the proliferation of clinics and marketing material trumpeting “T therapy” as an energy-boosting, anti-aging panacea (particularly in the US), testosterone is likely one of most widely abused banned substances among athletes.

The World Anti Doping Agency and national governing bodies do have a procedure in place to permit the use of banned substances for “medically appropriate” reasons, known as a Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE). A TUE for testosterone supplementation is virtually impossible to come by. And for good reason! Screw-ups like Cody 1.0 should not be permitted to chemically prop themselves up after overstepping their bodies’ natural thresholds.

Learn from my mistakes!

A silver lining to my story is that operating at a hormonal disadvantage has forced me to become very conscientious about the quality of my training, recovery, nutrition and equipment. Since other athletes could outclass me in training, my mindset was—and remains—that I simply can’t afford to sacrifice any other gain, no matter how marginal.

That philosophy has helped me find some success in triathlon despite training below the level of many of my peers. But I want to scale the heights of my potential. Building my fitness on a solid foundation of health is a flying leap towards that goal.

In summary, here are my observations and advice:

- Fuel workouts appropriately.

- Aim for a comprehensive blood test at least annually.

- Recovery, sleep and nutrition deserve just as much, if not more, attention than training.

- High level training without the supervision of a coach is playing with fire.

- Mental and physical health are inextricably linked.

- Don’t confuse fitness with health, but respect their relationship; peak fitness is built on a solid foundation of health.

- Embrace the never-ending process of seeking out and destroying your limiters, even if that entails radical change.

Please join the conversation about this post on Facebook, Twitter or in the comments below.

Appendix: Nutrition & supplements to increase testosterone

Several studies have associated low-fat diets with lower T levels [1,2,3,4] and have found significant correlations between fat intake and T levels [5,6]. (I won’t get into the changing picture of “good” and “bad” fats or what constitutes “high” or “low” fat diets.) Cholesterol is a chemical precursor for steroid hormones including testosterone, and there is some suggestion that higher dietary intake benefits T [1,2]. There is also some evidence that fish oil may increase T synthesis [1,2], in addition to a long list of other health benefits [3]. My diet used to be fairly low in fat, but I now include quality fat sources every day (e.g., avocado, olive oil, nuts, eggs, fish oil, higher fat dairy).

The relationship between protein and T is less with clear with studies reporting both higher [1] and lower [2] T on high protein diets.

It is commonly reported that soy contains phytoestrogens which can act as endocrine disruptors and hurt T [1]. Some studies have linked soy consumption with lower T [1,2,3], although the literature is by no means conclusive [3] and a 2010 meta-analysis found no ill effects on T [4]. Soy was once a staple in my diet, but I decided that the (small) potential risks made it worth avoiding, at least as my T levels recover.

Zinc deficiency is strongly associated with low T [1,2,3] and zinc supplementation has been shown to increase T [1,4,5,6,7], but perhaps only when zinc levels are suboptimal to begin with. (Caution: excessive zinc supplementation can deplete copper and have other negative effects [1].) Zinc deficiency is believed to be uncommon in North America [1], but vegetarians are at a greater risk [1,2]. Blood tests for zinc are difficult to interpret, although a simple “zinc taste test” can point to zinc deficiency [1], and it did in my case.

A popular supplement called ZMA, consisting of zinc, magnesium and vitamin B6, is purported to be a T booster based on a single highly questionable study [1] whose results have not been replicated in two subsequent studies [2,3].

Studies have shown a positive correlation between Vitamin D and testosterone levels [1,2] and that Vitamin D supplementation can increase T levels [3]. My only blood test for Vitamin D showed that my levels (90 nmol/L in 2014) were near the bottom of the optimal range [1,2] even after heavy supplementation for several months.

Studies suggest that testosterone has a positive effect on iron metabolism, hematocrit and hemoglobin [1,2,3,4], which are particularly important for endurance athletes. My serum ferritin (26 µg/L in 2012) was deficient by some definitions [1,2,3] and gradually returned to more optimal levels (66-75 µg/L) with iron supplementation. Although my test results have never indicated anemia, my hematocrit and hemoglobin (Hct 41% and Hb 140 g/L in 2014) are on the low side for male endurance athletes [1,2,3] and below my 2008 “baseline” values.

B vitamins are also commonly touted as a T booster; however, my research did not turn up clear link. Vegetarians need to pay attention to B vitamins [1,2,3,4], especially B12, but my levels have always tested well.

I’m also starting to drink coffee on a more regular basis. In addition to a growing list of health benefits, caffeinated coffee may have a positive effect on total T levels [1,2].