Two siblings, a nine year old boy and a seven year old girl, sit in the backseat of their parents’ car en route to their very first swim meet. Both are wide awake despite having passed a sleepless night for entirely different reasons. The little girl is positively bursting with excitement, bouncing in her seat, and babbling about all the events she will be swimming. The boy, on the other hand, stares balefully out the window with the look of the condemned, his trepidation mounting as their destination draws inexorably closer.

A couple hours later, the girl has swum her first event of the day. She is elated and promptly declares her intent to reach the Olympics.

The boy’s first event number is called and with wobbly legs and fluttery insides he takes a seat with his competitors on the pool deck. Each crack of the starter’s pistol heightens his sense that something terrible is about to happen. With the crystal clarity of adrenaline, he reaches a decision. Casually, as if stretching his legs, he rises from his chair and walks across the deck, through the gate and out of the building. He breaks into a sprint and makes for a nearby forest. There, hours later, his father discovers him sulking and nursing his wounded nine-year-old pride.

Several years later, the girl has matured into a promising young athlete and a fiery competitor. She sets regional swimming records and looks forward to her middle school’s Track & Field Day more than her birthday. She lives for racing.

Unlike his jock sister, the boy’s passions are reading, schoolwork and piano. He is the last to be chosen for games at recess. In eighth grade, he exploits a dubious leg injury to be excused from Track & Field Day. He has made a reluctant peace with competitive swimming and, although he shows some natural ability and work ethic, he lacks his sister’s competitive drive. He is among only a handful of geeks and misfits in his small town to not play hockey or lacrosse—deviant, borderline heretical behaviour that arouses the suspicion of his peers.

Now, in their early twenties, one sibling’s life revolves around training and racing, while the other has entirely abandoned competitive sports. The who, the why and the when may surprise you.

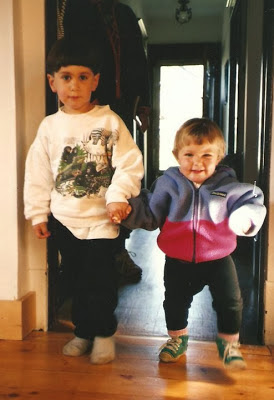

|

| The faces tell the whole story. |

You’ve probably guessed that I’m the bookish boy and the sporty girl is my sister, Genevieve. Yet, nearly fifteen years after our first swim meet, I’m the one pursuing elite-level triathlon while my sister hasn’t toed a start line in years. We were equally intrigued by what triggered this unexpected role reversal, so we sat down together to brainstorm some explanations. The ideas we came up with suggest that innate characteristics (nature), environmental factors (nurture) and chance (luck) all played important roles in shaping our divergent athletic trajectories.

This two-part piece will focus on the factors that account for our differences, but I should begin with our common background. Genevieve and I were introduced to endurance sports at a young age, shuffling along in skis almost as soon as we could toddle. My parents are both passionate athletes and role models for a healthy, self-propelled lifestyle. We were given every opportunity to discover sports in a supportive, low pressure environment.

Genetically, my sister and I can’t complain. My mother is an accomplished masters runner who boasted a sub-20 minute 5k into her late forties. My father is an avid cyclist who takes great pride in outstripping decades-younger men on local club rides.

Genevieve and I also share many traits—introversion, compulsiveness and a tendency to asceticism to name a few—but some key differences separated our paths in competitive endurance sports.

|

| The girl was a fearsome competitor and her brother was her greatest rival. |

Part I: The Jock, the Nerd & Lady Luck

The first fork in the road was more happenstance than anything else. Genevieve and I had two very different experiences with athletic competition during our early teenage years, a formative period during which the ego is fragile and powerful associations are forged.

To no one’s surprise, my sister quickly established herself as one of the top cross country runners in the district during her freshman season. The following year, her performance inexplicably began to decline to the point that she was struggling to finish workouts. Her enthusiasm for training and racing suffered along with her results.

She eventually recovered from her mystery ailment (likely iron deficiency anemia) and began to show promise again in grade 11 and 12, but the damage had been done. Not only had her athletic development taken a blow, but so had her self-confidence. Genevieve’s once raging competitive fire had all but fizzled out.

I didn’t even run cross country in ninth grade. The failure and embarrassment of trying out for the volleyball team the previous year was still fresh in my memory. No thank you, I was not a jock. In any case, I was too busy chasing top marks, playing piano and working my way through a pretentious reading list, all while trying hard to fit in at a new school (not entirely compatible activities). One fateful day in tenth grade set my life on a different course.

It all started when a boy on the cross country team had to drop out on the morning of the District Championships, leaving the team scrambling for a fourth runner. Coach Stride (his real name!) caught wind that some lanky kid had occasionally been spotted jogging around town.

I was sitting in first period math class when the entire cross country team burst in, frantically explained their predicament, and abducted me before I had any chance to formulate excuses. Before I knew it, I found myself on the start line of my first race wearing a borrowed pair of spikes. The race went as well as I could have hoped without any formal training. I finished a respectable top 20 and, more importantly, helped the team clinch the District Championships. I felt like a hero!

|

| An addict was born! I’m third from the left. |

Something clicked on that day. I had long found pleasure in individual sports, but athletic competition had always been intimidating—an arena of uncontrollable outcomes and potential failures. I suddenly realized that competition could be gratifying and exhilarating in ways I had never imagined. I also recognized that endurance sports, like my familiar academic sphere, rewarded consistent, deliberate practice even more than natural ability.

These revelations profoundly impacted my life over the years to come. By my senior year, I was a District All-Star in cross country and swimming and was dabbling in my first triathlons.

My sister’s prior athletic success had conditioned her to expect top results. Deprived of this consistent positive reinforcement, her competitive drive understandably faltered. Since I had no great expectations, one tiny taste of success set off fireworks in my brain’s reward center. Is it any surprise that an addict was born?

There’s no question that success in endurance sports requires a high level of intrinsic motivation. You have to love the process at least as much as the results. Nevertheless, a little external validation at the right time goes a long way towards instilling self-confidence and dedication.

That pivotal positive experience arose from having the right opportunity fall into my lap at just the right time. Would I have wound up a pro triathlete if I hadn’t stumbled onto that start line? Would my sister be still be a successful competitive athlete if it weren’t for that rough patch? Fortune, good and bad, touched both of us. As Malcolm Gladwell puts it in Outliers: The Story of Success:

“… success is not exceptional or mysterious. It is grounded in a web of advantages and inheritances, some deserved, some not, some earned, some just plain lucky”

Our role reversal can’t be entirely chalked up to chance. Even before that first swim meet, other forces were at play: psychological differences that a decade later would bring suffering and success in equal measure.

Part II: The Perfectionist & the Elephant in the Room